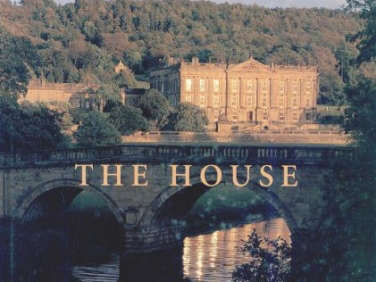

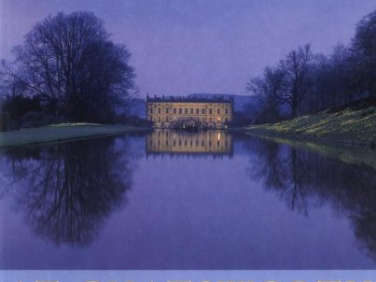

"Glorious" is a word that comes to mind whenever I visit Chatsworth. Not formidable and chilly like Versailles, but glorious. This is partly to do with the setting: from the west the honey-colored house appears to be nestled against the wooded hills, its gold-painted window frames reflecting the sun.

Perhaps you feel you've seen Chatsworth before? See A Grand Hollywood Backdrop: Chatsworth Plays Itself on Film.

Photographs by Kendra Wilson, for Gardenista.

Above: We are in Derbyshire in the Peak District of England's East Midlands. With its dramatic rocky landscape of waterfalls and moorland, this feels like a place which cannot be tamed, though the palatial box of Chatsworth sits very well in its midst. Garden designers who talk of the need to anchor a house to its surroundings need look no further.

The preoccupations of generations of owners is evident all over the park, from the 17th century Cascade (above) to the sculpture dotted around by the present duke. But it is the Dowager Duchess and her late husband the 11th Duke of Devonshire who were hugely responsible for bringing the garden (and house) back from the brink and ensuring future survival. The story of garden, house, and various occupants is written very engagingly in two books, The Garden at Chatsworth ($35 from Amazon) and The House at Chatsworth ($31.50 from Amazon). The Dowager Duchess is Debo, née Mitford, so she knows how to write about people and places.

"No one person designed the garden at Chatsworth," writes Deborah Devonshire in the Garden book. "It has evolved according to the taste of successive Dukes of Devonshire unshackled by committees." She laments the loss of the 17th century parterres around the house, swept away by Capability Brown. Fortunately, she says, he was so busy landscaping all the other stately homes in England that he didn't have time to demolish the Cascade and the dead straight line it forms down to the house and up the hill on the other side (see top picture).

Different layers of the garden remain, each reflecting the fashion or creative genius of the day. The west-facing Conservative Wall, above, is a lengthy series of shallow glasshouses built to protect espaliered apricots and peaches. They are decorative enough to be near the house and were designed by Joseph Paxton, head gardener. Later he was known as Sir Joseph Paxton, genius engineer, and designed the Crystal Palace for Queen Victoria in London's Hyde Park. During the Chatsworth years he built the Great Conservatory; constructed the enormously tall Emperor Fountain and re-built the village of Ensinor, across the valley from the house. The massive conservatory fell into disrepair after World War One and was torn down, its foundations remaining as a painful reminder (two pictures above; trees planted by Paxton have reached maturity).

The gardens at Chatsworth were built as pleasure gardens; the marvel of the place taking precedence over individual flower beds. Sometimes the sheer scale made it difficult for occupants to make their mark; Chatsworth was only one of several homes which needed attention in Ireland, Yorkshire, central London, Chiswick and neighboring Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. One ancestor laments in her diary, "We never really felt we had a home; as we had far too many."

The Trough Waterfall, above, was designed by the Dowager Duchess and the 11th Duke around the remains of a ravine garden created by a previous duchess, known as Granny Evie. They used water troughs gathered from fields around the estate.

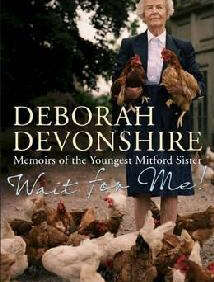

Deborah Devonshire (can we just call her Debo for short) found her writing feet with the publication of the Chatsworth books. No longer as conspicuously overshadowed by family writers Nancy, Jessica and Diana Mitford, she wrote increasingly in her later years at Chatsworth. On the publication of a book of recipes (or "receipts" as old-fashioned people call them) I went up to Derbyshire with the photographer Harry Borden to "art direct" a shoot for the Observer newspaper—though in truth designers were surplus to requirement. We were met by the butler and were given a rather reserved kind of welcome. Moving away from the formality of the West Garden the atmosphere improved. The photographer's assistant mentioned that she kept Rhode Island Red chickens in London and the duchess visibly relaxed, happy to be in the company of people who liked chickens. We took pictures among pigs and fowl, and Debo decided that we were worthy of a visit to the poultry house, a hexagonal stone building in the style of the main house, built solely for the comfort of the birds.

The picture which we used on the cover of Observer Food Monthly magazine and which Debo later chose for her memoirs (Wait for Me!) is of herself, carrying a chicken under each arm and looking perfectly content. Chickens are really her thing. There was some joking about the fact that I wasn't doing an awful lot (there wasn't much to do). Afterwards I mailed a print to Chatsworth as requested and soon after a small typed envelope appeared on my desk with gothic embossed lettering on the back: "Chatsworth, Bakewell." The note paper was so determinedly Old World that it looked quite eccentric to my eyes, though perfectly normal to a gentlewoman born in 1920. The phone number and local railway station were set at a 45-degree angle and the letter began: "Dear Miss Wilson, who stood about to some purpose…"

For more, see A Grand Hollywood Backdrop: Chatsworth Plays Itself on Film.

For the Mitford completist, see A Gothic Garden Visit, Courtesy of the Mitfords.

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation