This weekend, architect Rafe Churchill and designer Heide Hendricks, members of the Remodelista Architect/Designer Directory, talk to us about the design of a fully sustainable, color-filled farmhouse in rural New England. The two will be available for the next 48 hours to answer any and all questions. Ask away!

Seeking a retreat from the city, Churchill and Hendricks’s clients, a couple with two children, purchased a parcel of land with open fields and broad views in the northwestern corner of Connecticut on the Massachusetts border. Their vision of rural life included a net zero farmhouse and barns–structures that generate as much energy as they consume–along with a four-season garden with permaculture projects, composting beds, an orchard, and a managed forest.

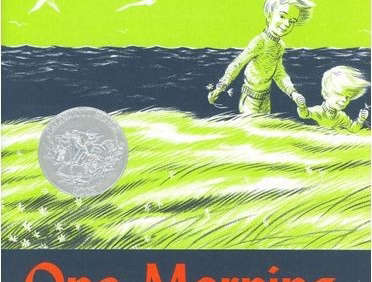

They also had a specific look in mind: the couple arrived at the first design meeting with Robert McCloskey’s classic children’s book One Morning in Maine and pointed to the illustrations of a sensible, simple farmhouse as exactly what they envisioned. Passionate about and committed to sustainable living, they also asked that their farmhouse include state-of-the-art green technology. “This house has a well-insulated exterior shell, a geothermal system, solar power, rainwater collection, a freshwater pool, and permaculture farming,” Churchill says. “We’ve seen many attempts at this program before, but the schemes often end up getting caught up in the technology, resulting in a modern farmhouse. We were determined to build a traditional farmhouse.”

“The approach for the interiors was on the spare and utilitarian,” Hendricks says. “Our several visits to Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, influenced our thinking. We had to accomplish a mood with very little decoration, so everything we brought in was completely necessary.”

Photographs by John Gruen.

Above: The look of the house is based on classic New England farms built at the turn of the 19th century. Churchill positioned the building toward the back corner of the open land, enabling the owners to capitalize on several views, including ponds, a nut grove, a small orchard, and a spectacular sunset.

Above: In developing the color palette for the project, Hendricks made site visits to study how the natural light affects each room throughout the day. During this early phase, she also made repeat trips to Hancock Shaker Village where she admired the Shakers innovative use of hits of color. “They used bold yellow oxide on the exteriors of some of their buildings, and introduced it inside on the trims and floors,” she says. “For this project, it was established early on that the plaster walls would be left pure chalky white and the trim would become the foil for introducing color.”

Above: In the kitchen, which is on the west side of the house, bright yellow cabinets and trim–painted in Babouche by Farrow and Ball–are contrasted with custom-fabricated black soapstone counters and sink. “Views out the window of meadows filled with goldenrod and black-eyed Susan helped choose the colors,” Hendricks says. “The yellow is brightest in the morning but then mellows to a mustard by the evening.” The ceiling pendants over the island are from PW Vintage Lighting and the faucet was sourced from Nor’East Architectural Salvage.

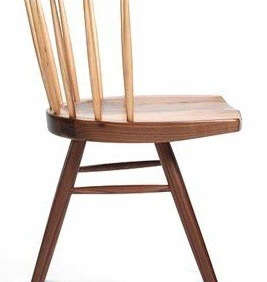

Above: The floors throughout the first level are Southern yellow pine finished with Bona Naturale. In the dining room, a Skygarden S Pendant lamp by Marcel Wanders hangs over a table made by Ralph Gorham of Brooklyn Farm Tables and George Nakashima Straight Chairs.

Above: A paneled wall with built-in shelves and drawers adds texture and warmth to the living room. As with yellow in the kitchen, the color in the living room–Folly Green, a discontinued Farrow and Ball shade–was selected in response to the room’s location on the east side of the house. “The view is of gardens and a seasonal stream with a wooded hillside backdrop,” Hendricks says. “We felt the room should be a place for lazy winter afternoons and long evenings by the fire, so we selected a cool, calming color.”

Above: Churchill incorporated his clients’ appreciation of Shaker irregular cabinetry into the room. “Knowing that this is a family house, I designed the drawers for storing board games and art supplies,” he says. “In a corner of the room, there’s a game table that’s often set up with an ongoing project or game.”

Above: The mudroom, the family’s primary entrance into the house, has a woodstove that keeps the space toasty and a Reclaimed Sawn Brick floor from Ecologie. “For whatever reason, when the owners are entertaining, this ends up being the room where the men and even the boys hang out,” Churchill says.

Above: Exposed framing in classic wood frame suggests that a room isn’t insulated. This net zero house, however, is well insulated: It’s constructed with Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs) that are hidden between the traditional shingle cladding on the exterior and the framing and sheathing, which are left visible in the mudroom. “The owner and his two boys have processed loads of kindling in this room,” says Churchill.

Above: The design of the stair rail was also influenced by Churchill and Hendricks’s visits to Hancock Shaker Village. The balusters are painted to separate them from the rail, which Churchill wanted to call out as a sculptural element. A window blind made from vintage lace is quietly impactful in this otherwise minimally decorated space.

Above: In keeping with the owners’ commitment to sustainability, Hendricks resolved to source all of the furnishings within a 100-mile radius. “Many of the purchases were made at secondhand stores, antiques centers, and estate sales,” she says. “For new furniture, we tried to select only manufacturers who follow green practices.” This bed was made by the Country Bed Shop of Ashby, Massachusetts, and the primitive side tables are from Hunter Bee of Millerton, New York. The black banker’s chair was found at Doodletown Farm Antiques in the Millerton Antiques Center, and the vintage rag rug came from the Housatonic Valley Rug Shop.

Above: Knowing that other technologies would be concealed within the house, the owners wanted the solar panels to be visible. Churchill installed a 10 kW solar array over a pre-weathered Galvalume standing-seam metal roof. “A solar array should only be installed over a new roof because the panels will outlast most roofing materials,” he notes. “Not only does a standing-seam roof outlast all other roofs but the system now also has aluminum mounting clips onto which panels can be mounted directly, meaning no holes in the roof. That’s a huge bonus for metal roofing.”

While the 10 kW solar grid generates enough power to run the electrical requirements of the house and the barn, including the geothermal system, the overall property falls short of being completely net zero because of the high-velocity circulation system required to run the freshwater pool. See Remodeling 101: Solar Paneling Primer and Hardscaping 101: Standing Seam Metal Roofs for more on both systems.

Above: The location of the screened porch on the south side keeps the house shaded. A “whole-house fan” in the attic also cools the interior: At the end of each hot summer day, the fan pulls in the fresh evening air and draws it up through the house. The daybeds from Hob Nail Antiques in Wingdale, New York, are covered in Sunbrella ticking fabric from Leslie Hoss Flood Interiors.

Above: “The decision to screen the porch was pretty obvious,” Churchill says. “Not only can it get pretty buggy after sunset but also the screening of the porch really adds to the intimacy of the space and allows for sleeping in the open air.” The table and chairs were a housewarming present that originally came from a family cabin where the owner of the house had spent his childhood gardening and exploring in the woods.

Above: On the exterior, the designers chose complementary colors: Yellow Oxide for the shingles and Flint for the door, both from Benjamin Moore.

Above: “When designing for sustainability,” Churchill says, “select the best materials and windows your budget can afford, and then find some more money to guarantee you stick to the program. A compromise on durability will undermine all efforts for long-term sustainability. We were fortunate that our clients understood this and were interested in learning with us.”

Above: The house has a classic New England farmhouse layout with public rooms on the first floor arrayed around a central hall.

Above: The four-bedroom second floor.

Above: An illustration from Robert McCloskey’s One Morning in Maine. Image via Betsy’s Cove.

For more on Structural Integrated Panel (SIP) construction, see Remodelista Architect/Designer Directory member Kimberly Peck’s barn conversion in The Architect Is In: A Rural Barn Transformed for Modern Living. Another favorite mudroom can be seen in the The Architect Is In: Romancing the Country in Nashville. And on Gardenista, have a look at 8 Nap-Worthy Summer Bunkhouses.

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (25)