London antiques dealer Will Fisher attributes his interest in interiors to a childhood encounter with a character named Warner Dailey, the father of his best friend. Fisher’s favorite saying—and a tenet he continues to live by—comes from Dailey: “I’m interested in things that look like they’ve grown roots on them.”

Photography by Simon Upton.

Jamb, the company Fisher runs with his wife, Charlotte Freemantle, has gained an international reputation for sourcing and reproducing such objects: rare fireplace mantels, 18th-century statuary, exquisite reproduction lighting, and country house furniture. Their gallery on the Pimlico Road in London’s Belgravia is frequented by celebrities and royalty, but Fisher is more likely to be found in their workshop in the lesser-known suburb of Mitcham. “It has become the throbbing heart of the company,” he says. “I find it utterly intoxicating to be in that environment, putting things together, working out how we can take objects and make them more appealing, more beautiful, more perfect in any way.”

Quality and surface are the two defining factors Fisher looks for and seeks to recreate: “We try and buy things that have avoided human intervention from the moment of their creation. That is very much a theme throughout our business and throughout our home.”

The couple live in a four-story Georgian terrace in Camberwell, south London. When they purchased the property in 2006, it was viewed as “the ugly duckling” of the street. (A Gothic Revival bay window and porch had been added to the purist Georgian facade.) But the couple both felt “unbelievably excited” by the interiors, which, although in “a state of decay” and stripped of original features, had managed to retain “a lot of soul.”

Fisher set about sourcing new-but-old surfaces, starting in the basement kitchen and working his way up through the four storys. He found a quantity of fossil-rich Purbeck stone, which he stored in a barn for several months, hand-selecting the slabs and having each piece individually milled before laying it throughout the basement level. “It looks enormously probable,” he says. “I don’t think anyone would ever come in the house and not think that the floor has always been there.”

The couple made the “emotionally and financially exhausting” decision to rebuild the interior walls with lathe and plaster. “It’s one of the most sympathetic things you can do to an old building—to allow it to breathe,” explains Fisher. “And it gives a fabulous feel to the entire house. When you look at the way the light hits the lime plaster, it is very, very different to the flat plane of a plastered wall. And light is everything, isn’t it? It really does set the tone for the entire house.”

Moving up through each story, they have adhered to what would have been the original hierarchy of the house. The kitchen retains the below stairs aesthetic of scrubbable surfaces and heavy, pared-back furniture. Then, as you ascend the stairs, the detailing on the doors and fireplaces becomes grander before quietening down again in the attic rooms. “Hopefully, it all kind of works and feels probable but still very sleepy,” says Fisher.

Their quintessentially British front room was redecorated during lockdown. “If you can’t change your location, change your environment,” reasoned Fisher. “We literally got above our station and went wildly over the top in a sort of English Palladian country house way,” he recalls. “We almost put on our powdered wigs—it was really fun.” The new mantle preempted a change of color, too. The walls went from pale slate to “the ultimate duck-egg blue.”

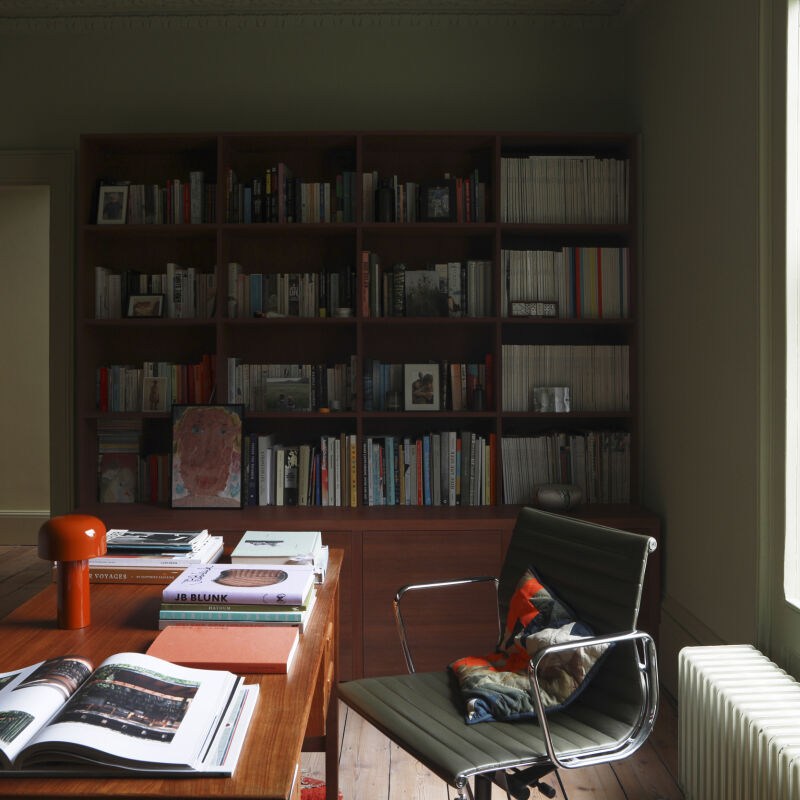

The drawing room is connected via double doors to the “tablet room.” (“That sounds slightly grandiose,” says Fisher. “It’s actually our TV room.”) Here, the walls are adorned with fragments of central tablets from chimney pieces. “It’s extraordinary how objects form so much of our identity,” says Fisher.“ After a hard day’s work, there’s something incredibly soothing about coming home and being surrounded by the things you love. I don’t think a day goes by that we don’t gain pleasure from the objects in this room.”

“Many objects have emotional attachment—not just for what they are, but for the circumstances in which they were procured,” says Fisher. The bust of Chrysippus was bought from an online auction while Fisher was in hospital with his son, Monty, then age three. “I have a rule that I don’t buy anything unless I—or somebody I trust implicitly—have seen it. But obviously the fact that we were in the hospital meant I had to take a leap of faith. The bust is very much a remembrance of that time. It also sort of encompasses Monty’s stoic behavior at that time.”

“There is a fundamental framework that we adhere to within the business and at home,” reflects Fisher. “Some of the things that enter the premises are planned, some aren’t. We’re never looking for something for a specific location: we’re more likely to find a specific item, and then find a location for it.” That said, the couple have over the years, sold off many of their personal possessions. The contents of their tablet room were auctioned off in 2012 (“we were both bereft”) and they have found themselves sofa-less on more than one occasion. “I don’t know why we ended up selling the sofas,” says Fisher. “It’s one of those ridiculous things, the temptation of an antique dealer. We’re fundamentally hawkers and traders. Also, we need something to sulk about. Life’s nothing without regret.

For more characterful English interiors, see:

An Eccentric Town House in Islington by Design Star Rachel Chudley

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (6)